Replicating scarcity

In Scarcity: Why having too little means so much, Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir tell the following (now famous) story:

To see the effect of scarcity on fluid intelligence, we ran some studies with our graduate student, Jiaying Zhao, in which we gave people in a New Jersey mall the Raven’s Progressive Matrices test. First, half the subjects were presented with simple hypothetical scenarios, such as this one:

Imagine that your car has some trouble, which requires a $300 service. Your auto insurance will cover half the cost. You need to decide whether to go ahead and get the car fixed, or take a chance and hope that it lasts for a while longer. How would you go about making such a decision? Financially, would it be an easy or a difficult decision for you to make?

We then followed this question with a series of Raven’s Matrices problems. Using self-reported household income, we divided subjects, by median split, into rich and poor. In this setup we found no statistically significant difference between the rich and poor mallgoers. …

For the remaining subjects, we ran the same study but with a slight twist. They were given this question instead (with the change shown in bold):

Imagine that your car has some trouble, which requires an expensive $3,000 service. Your auto insurance will cover half the cost. You need to decide whether to go ahead and get the car fixed, or take a chance and hope that it lasts for a while longer. How would you go about making such a decision? Financially, would it be an easy or a difficult decision for you to make?

All we have done here is replace the $300 with $3,000. Remarkably, this change affected the two groups differently. …

… The well-off subjects … did just as well here as if they had seen the easy scenario. The poorer subjects, on the other hand, did significantly worse. A small tickle of scarcity and all of a sudden they looked significantly less intelligent. …

We have run these studies numerous times, always with the same results. …

In all the replications, the effects were equally big. …

… our effects correspond to between 13 and 14 IQ points. By most commonly used descriptive classifications of IQ, 13 points can move you from the category of “average” to one labeled “superior” intelligence. Or, if you move in the other direction, losing 13 points can take you from “average” to a category labeled “borderline deficient.”

I have long considered this finding, drawn from a paper in Science by Mani and friends (2013) (pdf), to be one of the most unreliable findings in the behavioural sciences.

It fails the “effect is too large” heuristic. This can’t be anything but a massively biased effect size.

It relies on a prime. We have all seen how the priming literature has fared.

And despite the claim “We have run these studies numerous times, always with the same results”, for many years I’ve heard of failed replications and extensions stuffed into file drawers.

As a result, I’ve been keeping a keen eye on the topic and was excited to see a story about Leif Nelson and Don Moore training PhD students by doing a mass pre-registered replication of the scarcity literature. A great idea.

The result of that exercise has now been published in PNAS. The replication materials are available on OSF.

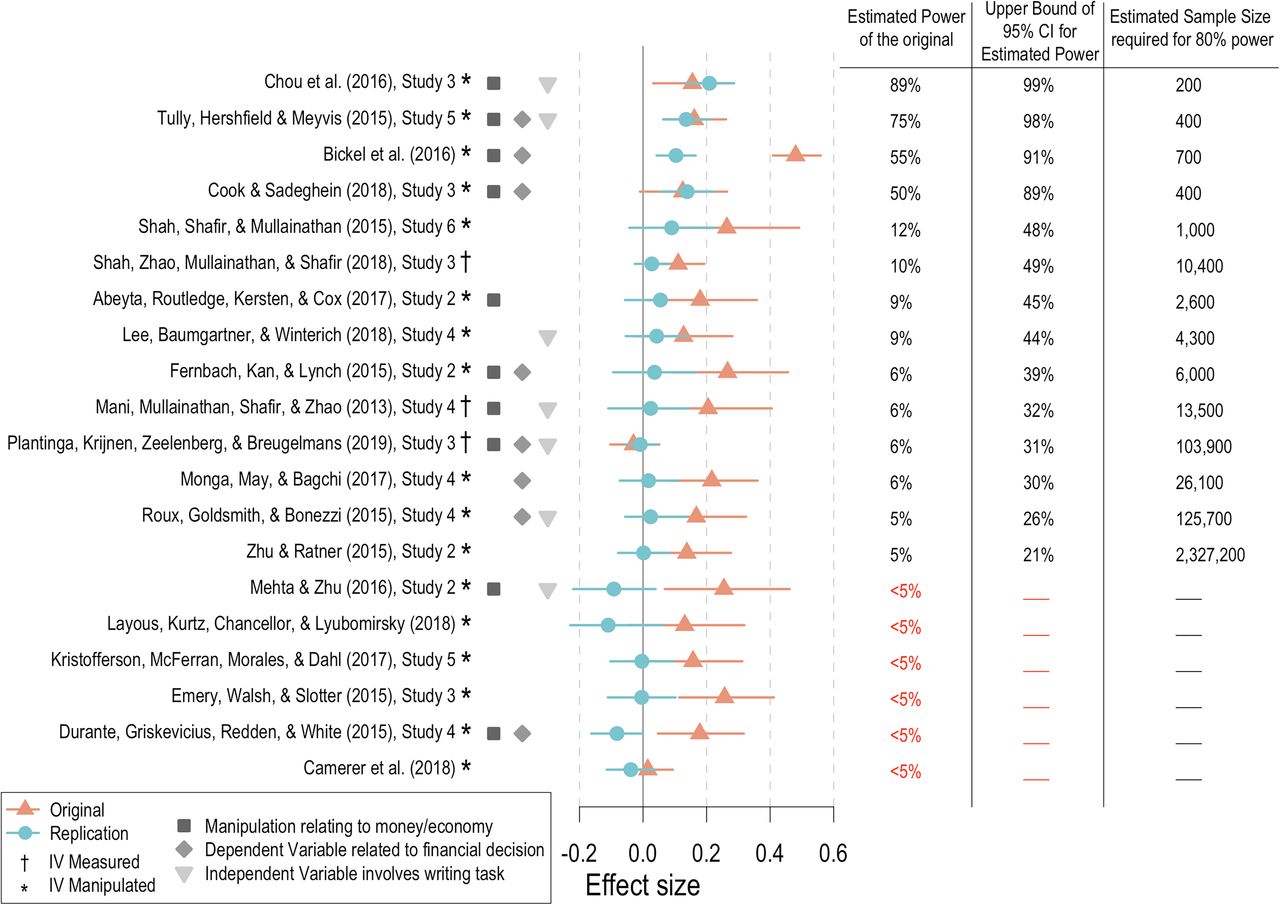

The punchline was that, of the 20 studies, only four generated a significant result. (That raw score of 20% is underperforming the replicability of social psychology.) This was despite the replications using 2.5 times the sample size of the original, giving them more power. Six studies had effects in the opposite direction to the original. Effect sizes were also markedly smaller, suggesting the initial experiments were massively underpowered. The following figure illustrates the results.

Study 4 from Mani and friends was one of the iterations of the New Jersey experiment and, as for most of them, there was no significant effect.

Summarising their findings, the authors write:

Scarcity is a real and enduring societal problem, yet our results suggest that behavioral scientists have not fully identified the underlying psychology. Although this project has neither the goal nor the capacity to “accept the null” hypothesis for any of these tests, the replications of these 20 studies indicate that within this set, scarcity primes have a minimal influence on cognitive ability, product attitudes, or well being. Nevertheless, feeling poor may influence financial and consumer decisions.

It’s not time to write off the concept of scarcity. A few of the results replicated, at least one them surprisingly so for me (economic insecurity causing physical pain). These were also lab experiments, so shouldn’t necessarily be used to ignore scarcity research from the field.

But it is time to take a more nuanced view of scarcity. The term captures what I consider to be several different phenomena. Which of these concepts might hold? And where? And it is definitely time to retire the story of a hypothetical car repair dropping a poor person’s IQ by 13 to 14 points.

On that more nuanced view, I have a rather long post (or possible review article) on scarcity in the works. This replication exercise is another great input. Hopefully my post will see the light of day this year.